Monday, December 25, 2006

This is it, Kids...

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Español,

NYC,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Holidays/Fiestas

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Español,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Friday, November 24, 2006

Parade Day/Dia del Desfile

For Thanksgiving Day, I went to the Macy's Parade (Grandstand, baby!) (Thanks Dan & Bill!)

Para Accion de Gracias, fui al Desfile de Macy's (Palco especial, no mas!) (Gracias a Dan & Bill)

I sat right on the stands at the "backdrop" of the NBC telecast of the parade, so I could go back home and replay the parade that was programmed on the digital TV recorder. And there I was, just behind Julie Andrews!!!

I sat right on the stands at the "backdrop" of the NBC telecast of the parade, so I could go back home and replay the parade that was programmed on the digital TV recorder. And there I was, just behind Julie Andrews!!!

Estuve sentado en los graderias que eran el telon de fondo de la transmision del desfile en NBC, asi que al regresar a casa, puse el desfile en la grabadora de TV digital que se quedo programada para grabarlo. Y ahi estaba yo, justo atras de Julie Andrews!!!

I realized that this is the second time I have "been" in U.S. National television, and the first time, of all things was also in a parade: the 1995 Hollywood Christmas Parade. Back then, digital cameras were not that usual, I guess...so the only picture I found, from the web, was the official group photo of the band I co-directed with my bud Luis. (I am the one on the right, without the uniform)

I realized that this is the second time I have "been" in U.S. National television, and the first time, of all things was also in a parade: the 1995 Hollywood Christmas Parade. Back then, digital cameras were not that usual, I guess...so the only picture I found, from the web, was the official group photo of the band I co-directed with my bud Luis. (I am the one on the right, without the uniform)

Me di cuenta que esta es la segunda vez que "aparezco" en la TV nacional de los Estados Unidos, y la primera vez, paradogicamente, tambien fue en un desfile: el Desfile de navidad de Hollywood de 1995. En ese entonces, las camaras digitales no eran tan comunes, creo yo...asi que la unica foto que encontre en la web fue esta, la foto oficual de la banda que co-dirigi con mi cuatazo Luis. (Yo soy el que esta sin uniforme a la derecha)

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Español,

NYC,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Thursday, November 09, 2006

New Religions, Performance Art and Social Activism

I've been always fascinated with the voice inflections, body language, and gimmicks of new fundamentalists, motivational speakers, and always try to concentrate on their technique. More than once it has come across my mind as performance art. The I found this clip of Reverend Billy and the Church of Stop Shopping. My first naive impression was that this was another crazy authentic religion. It turns out he is Bill Talen, a performance artist, who's turning into a high-powered anti-consumerism activist.

I liked this Talen's quote from an article published yesterday in The New Yorker magazine: “One time, I was arrested at a Buy Nothing Day Parade. We went in and exorcised a Starbucks cash register, and, sure enough, I got thrown in the holding tank at Fifty-fourth Street. And the cops that arrested me were really upset that they were missing this.” But this one, by Talen's associate, Reverend Michael O'Neill really caught my attention: “Community isn’t recognized unless it’s mediated through monetary transactions.”

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

Artes Escénicas,

NYC,

Performing Arts,

Vídeo

![]()

![]()

Friday, October 27, 2006

YouTube: Latin Youth Orchestras

Hace unos meses me suscribi en YouTube.com de modo que el webiste encontrara videos con descripciones que incluyeran las palabras "orquesta" y "sinfonica". Aca he escogido algunas orquestas infantiles y juveniles latinoamericanas que he encontrado. Los dos ultimos de Gustavo Dudamel con la Sinfonica Juvenil de Venezuela. La respuesta del publico no le envidia nada a la forma en que el publico respondio a Paul Simon en el Radio City Music Hall...

A couple of months ago I subscribed to YouTube.com, so that the website would find videos with descriptions that include the words "orquesta" and "sinfonica". Here I have chosen some youth and children's orchestras frfom Latin America. The last two clips are of Gustavo Dudamel conducting the Venezuela Youth Symphony. As for the audience cheers, they have nothing to envy compared to the response to Paul Simon at the Radio City Music Hall...

OSIM (Orquesta Sinfonica Infantil de Mexico/Mexico Children Symphony Orchestra)(Oct./ 22/2006)

"Fotos de la gira de la Orquesta Sinfonica Juvenil "Jorge Peña Hen" de la Universidad de la Serena, en el Septimo Encuentro Nacional de Orquestas en Antofagasta":

"Pictures of the Universidad de la Serena's 'Jorge Pena Hen' Youth Orchestra, ou tour to the 7th Nacional Orchestra Summit in Antofagasta":

Raúl Zurita, premio nacional de Literatura y Orquesta Antonio Vivaldi (publicado el 25 de oct. 2006)

Raul Zurita, national Literature Award and the Antonio Vivaldi Orchestra (posted Oct. 25th 2006)

"La Conga del Fuego Nuevo"-con la Orquesta Sinfonica Juvenil de Chiapas y la direccion Arturo Marquez- el autor(13 Ago. 2006)

"New Fire's Conga" with the Chiapas (Mexico) Youth Symphony, conducted by the composer(Aug. 13th, 2006)

Dudamel/Sinfonica juvenil de Venezuela: 5ta de Beethoven y ovacion (Mayo 2006)

Dudamel/Venezuela Youth Symphony: Beethoven's 5th and Cheer (May 2006)

Dudamel/Sinfonica Juvenil de Venezuela: Mambo (Mayo/May 2006)

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Paul Simon en/in Radio City Music Hall

Stephen took me this time to the Paul Simon concert at RCMH. It was fun!

Picture of the concert by Rahav Segev, as published in the New York Times |

Picture of the concert by me, as published in this blog |

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Music,

Música,

NYC

![]()

![]()

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Paso' una semana llena de emociones!

Que semana fue esta!!

El lunes Stephen me invito' al Concierto de Barbra Streisand en Madison Square Garden. Aunque su articulo (con que el que estoy 200% de acuerdo) no fue muy favorable (de hecho, el concierto fue una mierda...), bueno...era la Streisand....Oprah y su famosa amiga estaban ahi en primera fila, asi' como Tony Bennet, Audra MacDonald, Diana Krall y Rosie O'Donell(si, a todos ellos los podia ver desde mi lugar)

Streisand en escena |

Streisand en la pantalla (cerca de la ENORME pantalla/apuntador) |

Tony Bennett y Diana Krall |

El martes fue una de esas ocasiones en las que agradezco haber elegido la carrera que elegi. La tienda de Baccarat en Madison Avenue organizo un evento benefico para Orpheus. el quinteto de vientos de la orquesta interpreto' cuatro movimientos de "La Tumba de Cuperin" de Ravel. Fue un deleite. La mezcla de impresionismo Frances en el marco de cristal fino frances que unica.

|

|

El miercoles Stephen me invito al concierto de Audra MacDonald en la Sala Allen del Jazz at Lincoln Center. Este escenario tiene como telon de fondo una vidriera gigantezca que ofrece una vista espectacular del Parque Central y de la Calle 59. El concierto estuvo magnifico. No se puede comparar con la presentacion tan bochornosa de la Streisand.

El jueves fue el conceirto de paretura de la temporada de Orpheus en Carnegie Hall, que se presento con Emanuel Ax interpertando dos Concewritos para piano de Mozart, ademas de la Obertura de Cosi fan Tutte y la Sinfonia "Haffner".

Y el viernes, consegui un boleto para la presentacion de la compañia de danza de Merce Cunningham, en la presento su pieza con iPods. El publico tenia que bajar la musica del website de Cunningham, o prestar uno en la entrada del teatro. La presentacion tambien incluia musica amplificada en la sala, asi que la partitura es una mezcla de lo que cada persona escucha en su iPod, con la musica en la sala. Una experiencia verdaderamente unica para cada persona.

Y hoy, domingo, tuve una presentacion con la orquesta New York Symphonic Arts Ensemble en el lado este. Tocamos la 6ta de Tchaikovsky, y el 2do Concierto para piano de Chopin.

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

Español,

Music,

NYC,

Orpheus

![]()

![]()

An exciting week went by!!

What an great week this was for me!

On Monday Stephen took me to the Barbra Streisand concert at Madison Square Garden. Although his review (with which I agree 200%) was not favorable (actually the concert sucked!), it was Barbra...well...whatever. Oprah and her friend were there, Tony Bennett was there, Audra MacDonald and Diana Krall were there, Rosie O'Donell was there (yes I could see them all from my seat!)...

Streisand on stage |

Streisand on screen (next to the HUGE teleprompter) |

Tony Bennett and Diana Krall |

Tuesday was one of those days that you are thankful of being in the career you are. The Baccarat store on Madison Avenue organized a benefit event for Orpheus. The orchestra's wind quintet performed 4 movements of Ravel's Le Tombeau de Couperin. It was delightful. The mix of French impressionism and French fine glass was unique.

|

|

On Wednesday Stephen took me to Audra MacDonald's concert at the Allen Room, in Jazz at Lincoln Center. Once again, I was mesmerized by the view of Central Park as the visual background for the concert. She was fantastic, cannot compare to Barbra's lousy, cheesy, ridiculous performance (well, there, I compared it...)

On Thursday, Orpheus had its Season Opening Concert at Carnegie Hall, with Emanuel Ax playing two Mozart Piano Concertos, plus Orpheus playing the Overture to Cosi fan Tutte and the ""Haffner" Symphony.

And, on Friday I got tickets to Merce Cunningham's show at the Joyce Theater, in which they premiered Cunningham's new "iPod" piece. Audience either downlodad the score from Cunningham's website, or could get an iPod shuffle at the entrance. The score also included amplified music, so you could have a unique expeirence of the piece, by mixing the sound from your ipod, with the msuic from the Pa system with the dance.

And today, Sunday, I just had a performance with the New York Symphonic Arts Ensemble on the east side. We played Tchaikovsky's Pathetique, and Chopin 2nd Piano Concerto.

It was a fun, busy week!

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Music,

NYC,

Orpheus

![]()

![]()

Saturday, October 14, 2006

A landmark in Music History?

Un hito en la historia de la musica?

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

NYC,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Friday, September 01, 2006

Politicas del Arte que responden a movimientos sociales

Uno de los resultados de un movimiento social es la creación de políticas: Los movimientos laborales buscan que se creen leyes que mejoren las condiciones de los trabajadores, los movimientos indígenas buscan (entre otras cosas) que se reconozcan legalmente los derechos de sus pueblos, etc. Claro está, los movimientos sociales tambien buscan un cambio en el seno de la sociedad: que cada individuo sea un agente de las mejoras que busca el movimiento. Como este blog se refiere a polítcas del arte, no voy a entrar en detalle de los cambios sociales (y culturales) que propician los movimientos sociales.

Mi movimiento social favorito que ha propiciado políticas, es el sistema de orquestas sinfónicas de Venezuela. Inició en los 1970s como un movimiento de orquestas infantiles y juveniles, hasta que consiguió institucionalizarse, y convertise (como cosa peculiar) en parte del Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social de Venezuela, hace ya mas de 10 años. El sistema inicio con individuos organizando orquestas por toda Venezuela, siguiendo una misión, y sistema de enseñanza y gestión común, hasta que sus alcances fueron reconocidos y puestos en blanco y negro, en decretos, leyes, acuerdos, etc. que formalizaron la institucinalizacion de la "Fundación del Estado para el Sistema Nacional de Orquestas Infantiles y Juveniles de Venezuela".

Un caso contrastante fue el movimiento de artistas contemporáneos, en parte surgidos del Festival "OctubreAzul", en Guatemala, que en 2002 evitó que se promulgara una ley para regular manifestaciones obscenas.

Otros movimientos sociales que han generado politicas de arte:

- En general, los movimientos laborales en Estados Unidos han generado políticas relacionadas con los diversos sindicatos de trabajadores en las artes (musicos, bailarines, trabajadores de tramoya, etc), que han propiciado cambios en la practica y gestion de las artes.

-

Monday, August 28, 2006

Gustavo Dudamel en Tanglewood

Del 24 al 27 de Agosto, Stephen y yo manejamos a Lenox, Massachussetts, para asistir al debut de Gustavo Dudamel dirigiendo a la Sinfónica de Boston. El concierto abrio con la Obertura de Candide de Bernstein, el Concierto No. 1 para Piano de Beethoven (Imogen Cooper, solista) y cerró con El Amor Brujo de De Falla. En la tienda de Tanglewood me encontre con el disco debut de Dudamel con la Sinfonica Juvenil de Venezuela para Deutsche Grammophon, recien salido del horno. Las críticas del concierto y del CD han sido muy favorables. Asi que salimos muy contentos del concierto: La orquesta magnifica, Dudamel magnífico, la acústica impecable, y las críticas maravillosas. Hasta encontramos vecinos de nuestro edificio en Nueva York sentados a unos metros de nosotros!

En Tanglewood tambien vimos a Emanuel Ax tocando en 2do. concierto para Piano de Beethoven, dirigido por Herbert Blomstedt, quien tambien dirigió la 7ma. Sinfonía de Bruchner.

En cuanto a los Berkshires (la region de Massachussetts donde queda Tanglewood), visitamos la residencia de la escritora Edith Wharton, quien ademas fue una de las precursoras del la arquitecutra paisajista. Tambien fuimos a ver una obra de teatro en el Festivasl de Teatro de los Berkshires, y otra en Williamstown.

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

El Sistema,

Español,

Música,

NYC

![]()

![]()

Sunday, July 23, 2006

Arts Policies with ideological/political goals (Where do Arts Policies come from, Part 2)

Continuing with the subject of Where do Arts Policies come from, I am convinced that the first and main motivation to create Arts policies is to respond to political and/or ideological interests. No doubt in my mind. Where I have a doubt is in whether these interests are transparent, or if they are only a matter of keeping an image.

In the first class of my Issues of Cultural Policy at Columbia University, taguth by Dr. Ruth Bereson (now director of the program in Arts Management at the University at Buffalo), she read us a series on statements from different countries. The task was to try to id where each came from. The goal was to understand the natureof these statements, many times connected with the social, political, and economic times (and places), and many times the complete opposite. What is common, and was evident by reading the statements out of their context, is that they have a heavy ideological and political load: Their promise is to strengthen and protect national identities.

My final essay for the course questions the frank-ness of many of these policies. A lot of them were created to favor the public image of the ruling party (locally, but also abroad), but I doubt that, in most cases, the creators of such policies are prepared (intellectually and animically) to implement such rules.

One example: in 1961 Andre Malraux, the first Miniter of CUlture of France, opened the first of many Houses of Culture, with the idea of de-centralize the administration and promotion of the French culture. The success or failure of this policy has been subject of many debate, which are not relevant here. In 1970, 9 years later, the first House of Culture opens in Guatemala. My argument (perhaps a bit cynical): The replication of this policy only pretends to give the impression that Guatemala was "moving forward", just because they were following european models. To date, the Houses of Culture in Guatemala remain without a clear mission or overall goal, without a frank reason d'etre. What is clear in my mind is that some politician's (or bureaucrat's) resume includes his/her participation in the drafting of the decree for the creation of one of all of the Guatemalan Houses of Culture.

One example: in 1961 Andre Malraux, the first Miniter of CUlture of France, opened the first of many Houses of Culture, with the idea of de-centralize the administration and promotion of the French culture. The success or failure of this policy has been subject of many debate, which are not relevant here. In 1970, 9 years later, the first House of Culture opens in Guatemala. My argument (perhaps a bit cynical): The replication of this policy only pretends to give the impression that Guatemala was "moving forward", just because they were following european models. To date, the Houses of Culture in Guatemala remain without a clear mission or overall goal, without a frank reason d'etre. What is clear in my mind is that some politician's (or bureaucrat's) resume includes his/her participation in the drafting of the decree for the creation of one of all of the Guatemalan Houses of Culture.

Políticas del Arte con fines ideológicos/políticos (De dónde vienen las políticas del Arte, Parte 2)

Continuando con el tema De dónde vienen las politicas del Arte, me parece que la primera y principal motivación para la creación de políticas del arte es atender intereses políticos y/o ideológicos. De eso no hay menor duda. De lo que sí la hay es si esos intereses son transparentes, o si sólo son pura cuestión de imagen.

En la primera clase de mi curso de Políticas Culturales en la Universidad de Columbia, impartido por la Dra. Ruth Bereson (ahora Directora del programa de Gestión para las Artes en la Universidad de Buffalo) nos leyó una serie de enunciados de diferentes paises. La tarea era tratar de identificar de qué país venía cada una. El objetivo era comprender la naturaleza de estos enunciados, muchas veces conectados con la realidad social, política y económica del momento (y el lugar), y muchas veces todo lo contrario. Lo que es común, y fué evidente al leer los enunciados fuera de contexto, es que los enunciados tenían una carga ideológica y política: Pretenden fortalecer y proteger identidades nacionales.

Mi ensayo de fin de curso questiona la franqueza de muchas de estas políticas. Muchas de ellas estan hechas para favorecer la imagen pública del partido (a nivel nacional e internacional), pero personalmente, dudo que los creadores de estas políticas esten preparados (intelectual y animicamente) para implementar tales reglas.

Un ejemplo: en 1961 André Malraux, el primer Ministro de Cultura de Francia abrió la primera de muchas Casas de la Cultura con la idea de decentralizar la administracion y promoción de la cultura francesa. El éxito o fracaso de esta política ha sido tema de muchos debates, que no vienen al caso. En 1970, 9 años después, se inaugura la primera Casa de la Cultura en Guatemala. Mi propuesta (quizas un tanto cínica): La réplica de esta política, en el fondo, lo único que perseguía era dar la impresión que Guatemala estaba progresando, sólo por el hecho de seguir modelos europeos. Hoy día las Casas de la Cultura en Guatemala siguen sin piés ni cabeza, sin norte, sin razón franca de existir. Lo que sí es seguro que más de algún político (o algún burócrata) ha incluído en su curriculum su participación en la elaboración del decreto de creación de una o todas las Casas de la Cultura.

Un ejemplo: en 1961 André Malraux, el primer Ministro de Cultura de Francia abrió la primera de muchas Casas de la Cultura con la idea de decentralizar la administracion y promoción de la cultura francesa. El éxito o fracaso de esta política ha sido tema de muchos debates, que no vienen al caso. En 1970, 9 años después, se inaugura la primera Casa de la Cultura en Guatemala. Mi propuesta (quizas un tanto cínica): La réplica de esta política, en el fondo, lo único que perseguía era dar la impresión que Guatemala estaba progresando, sólo por el hecho de seguir modelos europeos. Hoy día las Casas de la Cultura en Guatemala siguen sin piés ni cabeza, sin norte, sin razón franca de existir. Lo que sí es seguro que más de algún político (o algún burócrata) ha incluído en su curriculum su participación en la elaboración del decreto de creación de una o todas las Casas de la Cultura.

Warm Up at P.S.1

Warm Up en P.S.1

Yesterday I went to the P.S.1 Warm Up, invited by my Arts Administration classmate Yng-Ru Chen, who works now as the Director of PR at P.S.1. In spite of the dangerous storm threats, the rain, and the recent power shutdowns in Queens, the Warm Up was well attended and fun.

Ayer fui al Warm Up de P.S.1, invitado por mi compañera de clase de Arts Administration, Yng-Ru Chen, quien trabaja como directora de relaciones públicas de P.S.1. A pesar de las amenazas de tormentas, de la lluvia y de los apagones recientes en Queens, el Warm Up recibio bastantes visitantes, y fue divertido.

DJs included A Guy Called Gerald “live”(Sugoi, U.K. Berlin)San Serac “live” (Output, Boston)and Derek Plaslaiko (Ghostly, NYC). At the entrance of P.S.1, I enjoyed the view of the installation of MoMA's Seventh Annual Young Architects Program winners (OBRA), called Beatfuse!.

Los DJs que participaron incluyeron a A Guy Called Gerald “live”(Sugoi, U.K. Berlin) San Serac “live” (Output, Boston)and Derek Plaslaiko (Ghostly, NYC). En la entrada de P.S.1, disfruté de la vista de la instalación "Beatfuse!" (por la firma OBRA), que fue la ganadora del Séptimo Programa Anual de Arquitectos Jóvenes del MoMA.

When visitng the exhibits I was surprised to find a video of Guatemalan Regina Galindo's performance "Quien puede borrar las huellas?" I'll write more about that.

Al visitar las exhibiciones, me sorprendió encontrar un vídeo de la performance de la Guatemalteca Regina Galindo, "Quién puede borrar las huellas?" Ya escribiré más sobre eso.

1 comments/Comentarios

Labels:

NYC,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Friday, July 07, 2006

Orquesta de Barro/Clay Orchestra

(Trujillo, Peru)

Hace unos meses descubri esta orquesta con los mismos pricipios de Accion Social por la Musica, en You Tube, y he querido escribir acerca de ellos en mi blog. Hasta ahora he aprendido a poner videos de You Tube aca. El video es elocuente.

A few months ago I discovered this orchestra with the same principles of Social Action Through Music inYou Tube, and I have wanted to write about them in my blog. I just learned how to attach videos from You Tube here. The video speaks for itself (even if in Spanish, but if not, what you really need to know is that the professors are members of the Trujillo Symphony Orchestra, the program is funded by private entities and they need money).

Friday, June 30, 2006

Madonna:

que puedo decir?

what can i say?

Hace dos noches fuimos al concierto de Madonna en Madison Square Garden. Mil Gracias a Liz Rosenberg....

Two nights ago we attended Madonna's concert in Madison Square Garden. Thanks a lot to Liz Rosenberg...

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

NYC,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Orquestas Comuntarias en la Ciudad de Nueva York (o: "mi participacion REAL en las Artes")

De acuerdo con el establecimineto de las Artes en Estados Unidos, "Participacion en las Artes" se refiere al publico. No estoy exactamente seguro de porque le llaman "particiapcion". Tampoco estoy seguro que es, entonces, lo que estan haciendo todas las gentes que tocan el las tantas orquestas comunitarias en la Ciudad de Nueva York. A mi me parece que estan participando, sin ser parte del publico...

Desde que empece a tocar en Nueva York, he participado en 5 orquestas, desde substituto en un ensayo de una, hasta percusionista en una temporada completa en otra. Estas son "mis" orquestas en Nueva York:

La Orquesta-Taller del 92nd Street Y (Direcor Artistico: John Jaffe): En su 89no. año, esta orquesta se dedica a leer nuevo repertorio cada domingo por la mañana (nuevo repertorio cada semana). Hetocado muchas cosas, como Los Pinos de Roma de Respighi, la Guia de la Orquesta Para los Jovenes de B. Britten, el Concerito para Orquesta de Bartok y Los Planetas de G. Holst. Son solo dos conciertos abiertos al publico al año, pero cada domingo es emocionante!

En esta orquesta conoci a Alan Bergman, un abogado de derechos de autor, bateriista de jazz y Timbalista/Presidente del Consejo de la Orquesta New York Symphonic Arts Ensemble, (Sybille WErner, Directora Musical). He tocado dos conciertos y cubierto a Alan en un par de ensayos. En esta orquesta he tocado musica de Sibelius, Frede Grofe (El Gran Cañon), entre otros.

Alan tambien me presento con David Lebowitz, director musical de la Orquesta New York Repertory. Con ellos solo toque un hueso, y mi debut en Radio City Music Hall!! Toque para la Gala Global del Año Nuevo Chino. No fue el debut de mis sueños en esa sala, pero fue una buena experiencia.

A traves de mi colega James Eng en la Orquesta de Camara Orpheus, fui invitado a tocar en la Orquesta Musica Bella de Nueva York (Philip Gaskill, Director Musical). Desafortunadamente, dos orquestas tenian conciertos el mismo dia, asi que no pudo continuar con Musica Bella...

Por ultimo, James me invito a tocar con la Orquesta Comunitaria del Conservatorio de Brooklyn, este pasado fin de semana. Tocamos El Lago de los Cisnes completa, y la orqyesta tambien toco la Overtura Don Giovanni de Mozart y el Concierto para Violin de Brahms.

Parece que hay un monton mas de orquestas como estas en los Estados Unidos. La gente de Arte "superior" no toman muy en serio a estas agrupaciones, estupidamente, tengo que decir, pues tienen un potencial para cultivar publico de mucho valor, y deberian ser la conexioin real entre las grandes organizaciones para las artes y sus comunidades.

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

Desarrollo de Público,

Español,

Música,

NYC

![]()

![]()

Monday, June 19, 2006

Community Orchestras in New York City (or: "my ACTUAL participation in the Arts")

According to the American Art establishment, "Participation in the Arts" refers to the audience. I am not exactly sure why do they call it participation. I am not sure either what are the people playing in the many community orchestras in New York City doing. It seems like they are participating, but they are certainly not the audience...

Since I restarted playing in New York, I have participated in 5 orchestras, from filling in for one rehearsal to a whole season. This are "my" orchestras in New York City:

The 92nd Street Y Workshop Orchestra (John Yaffe', Artistic Director): At their 89th year, this orchestra is dedicated to read repertoire each Sunday morning (new repertoire every week). I've played so many things, from Respighi's the Pines of Rome, to Britten's Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra, and from Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra to Holst "the Planets". Only two public concerts per year, but exciting stuff every Sunday!

At the 92nd Y Orchestra, I met Alan Bergman, a copyright lawyer, jazz drummer and timpanist/President of the board of the New York Symphonic Arts Ensemble Orchestra, (Sybille Werner, Music Director). I have played two concerts and covered Alan in a couple of rehearsals. There I have played music from Sibelius, Frede Grofe (Grand Canyon), among others.

Also through Alan I was introduced to David Leibowitz, Music director of the New York Repertory Orchestra. With them I only played one Timpani gig, and my debut at the Radio City Muysic Hall! There we played at the 2006 Chinese New Year Global Gala. Not my dream debut at that venue, but was a fun experience.

Through my collegue James Eng at the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra office, I was invited to play at the Musica Bella Orchestra of New York (Philip Gaskill, Music Director). Unfortunately, Two orchestras had their concerts on the same day, so I couldn't continue with Musica Bella...

Lastly, last week, James invited me to perform at the Brooklyn Conservatory of Music Community Orchestra, this past weekend. I played only in "The Swan Lake", but the orchestra also played Mozart's Don Giovanni Overture and the Brahms Violin Concerto.

And it seems like there are a lot more of orchestras like this all over the United States. High-brow arts people look down at this arts community, stupidly, I have to say, since this are really valuable potential audience and should be the real connection between the large professional arts organizations and their communities.

Friday, June 16, 2006

Rufus Wainwright: L.H.O.O.Q.

It is one of those funny coincidences that Rufus Wanwright's Tribute to Judy Garland Concert in Carnegie Hall happened only a couple of days before the opening of a big Dada exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. I had the fortune to attend the first of two concerts offered by Rufus. Since I am (still) reading The Art Firm (see "History Backwards", in this blog), I spent the concert trying to look at the big picture: Rufus is not a great singer, I never heard Judy Garland's Carnegie Hall concert (which Rufus reproduced, at least in the order of the songs and by using the same orchestra arrangements, transposed). So no, it was not a great concert. "Is this Art or entertainment?" I kept thinking. Then I thought of it as a performance art piece, less about beauty and technique, but more about making a political statement. As Stephen (Holden) told me, it IS a big deal that a man is standing there doing what most of the people in the audience have fantisized about (I think 85-90% of the audience was gay, over 30).

It is one of those funny coincidences that Rufus Wanwright's Tribute to Judy Garland Concert in Carnegie Hall happened only a couple of days before the opening of a big Dada exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. I had the fortune to attend the first of two concerts offered by Rufus. Since I am (still) reading The Art Firm (see "History Backwards", in this blog), I spent the concert trying to look at the big picture: Rufus is not a great singer, I never heard Judy Garland's Carnegie Hall concert (which Rufus reproduced, at least in the order of the songs and by using the same orchestra arrangements, transposed). So no, it was not a great concert. "Is this Art or entertainment?" I kept thinking. Then I thought of it as a performance art piece, less about beauty and technique, but more about making a political statement. As Stephen (Holden) told me, it IS a big deal that a man is standing there doing what most of the people in the audience have fantisized about (I think 85-90% of the audience was gay, over 30).

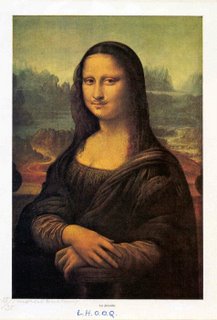

Then, Duchamp and his moustached Mona Lisa (Called "L.H.O.O.Q", read in French: "Elle a chaud au cul", could be translated as "She's got a hot ass") came to my mind. I found it hilarious: Duchamp's Moustached Mona Lisa is to the original Mona Lisa, what Rufus' tribute concert is to Judy Garland's 1961 Carnegie Hall concert.

Then, Duchamp and his moustached Mona Lisa (Called "L.H.O.O.Q", read in French: "Elle a chaud au cul", could be translated as "She's got a hot ass") came to my mind. I found it hilarious: Duchamp's Moustached Mona Lisa is to the original Mona Lisa, what Rufus' tribute concert is to Judy Garland's 1961 Carnegie Hall concert.

As for the MoMA exhibit, which opens this weekend, I won't be missing it!

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Music,

NYC,

Opinion

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

De donde vienen las politicas del arte?

Siempre me dió la impresión que en Guatemala se esperaba que las políticas culturales (y del arte) fueran un librito con instrucciones con todas las soluciones para el sector, y que nadie se había tomado la molestia de escribirlas. A finales de los 1990s iniciaron los congresos, talleres y planes estratégicos para discutir e idealmente producir este librito (al menos, porque implementarlas realisticamente sería otra historia). En el documento final "Políticas Culturales y Deportivas Nacionales", publicado en 2000 por el Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, la palabra "arte" se menciona tres veces, y la palabra "artista" seis.

En próximos artículos, voy a intentar examinar con detalle las políticas de las artes en Guatemala. Y no me refiero solamente a las que fueron producto de estos congresos, seminarios y planes estratégicos, sino ademas de todas las demas que andan flotando, o estan escondidas por ahí, y nadie ha sacado provecho de ellas. Espero encontrarme con buenas sorpresas. Pero, tanto en Guatemala, como en otros países, ¿de dónde vienen las políticas de las artes? Principalmente, estan hechas de leyes tanto nacionales como locales y acuerdos diplomáticos y regulaciones internacionales. Muchas no tienen nada que ver con arte o cultura: Leyes de impuestos, tratados de libre comercio, regulaciones urbanas, leyes en educación y desarrollo social. Aun así, se deben considerar qué "fuerzas" tienen influencia en el quehacer de las artes, y se deberían considerar como los motores de las políticas de arte. Yo me atravería a ponerlas en cuatro categorias:

1. Regulaciones y leyes que fueron ideadas con fines ideológicos/políticos y/u organizacionales.

2. Preservación de tradiciones, costumbres y cánones. (Cultura local y global, tradiciones y cánones artísticas)

3. Tendencias del Mercado de las Artes (qué, cuándo, cómo y cuánto arte se ofrece, y quién esta dispuesto a "consumirlo", bajo qué condiciones, con qué frecuencia, a qué costo, etc.)

4. Movimientos Sociales (movimientos de artistas, u organizaciones que prentenden cambiar el status quo del quehacer de las artes, y en consecuencia producen cambios en cualquiera de los tres factores anteriores)

Where do Arts policies come from?

I always had the impression that in Guatemala people expected cultural (and arts) policy to be a little book of instructions with all the solutions to the arts sector, and that no one had taken time to get to write them. Then they started the strategic plannings, seminars and congresses in order to produce this so-expected little book. In the final document, the word "art" is mentioned less than 10 times, I think (I may be wrong, but that is the impression I got when I checked the document that was out there for a while). En future articles, I will try to examine in detail the policies related to the arts in Guatemala. And I am not refering only to the ones that are a product of those strategic planning seminars and congresses, but also other laws that are floating out there, or hiden somewhere and nobody has taken advantage of them. I look forward to find good surprises. But, where do arts policies come from? Mainly they come from the legal system, both national and local, and diplomacy agreements and international regulations. A lot of them have nothing to do with arts or culture. Still, one should consider which "forces" have an infuence in arts making, and should be considered the "engines" of arts policy. I can think of four categories:

1. Regulations and laws (created with ideological/political and/or organizational goals)

2. Local culture (Traditions and customs of the people that practices, attends and/or supportsthe arts)

3. Arts market trends (what, when, how and how much art is out there, and who is willing to "consume" it, under what conditions, how often, to what cost, etc)

4. Social movements (movements or artists or arts organizations that pretend to change the status quo of arts making, and in consequence produce changes in any of the three above mentioned factors)

Sunday, June 11, 2006

Comments on Social Action Through Music and Cultural Policy, Part 1 (From my Masters Essay)

In the last 10 years, several performing arts projects with a social development component have appeared throughout the world. Arts administrators should be aware of these trends and pay close attention to how international organizations that provide financial support to social development programs are interacting with arts organizations in the Third World, and giving shape to a new cultural policy paradigm.

It has been almost two decades since Nestor Garcia Canclini offered the first broad critical analysis of cultural policies in Latin America (García Canclini, N. (1987). Políticas culturales en América Latina [Cultural Policy in Latin America] (1a. ed.). México: Grijalbo). In his analysis, he outlines six paradigms for the origins, agents, organizational structures and goals of cultural policies in Latin countries. Although it is not Garcia Canclini’s intention, it is easy to trace a certain historical evolution in those paradigms by examining the first –mecenazgo liberal (liberal patronage)– and the last –democracia participativa (Participative Democracy). The liberal patronage paradigm can be traced back to the Middle Ages, although it still survives in the United States and other countries where the state is not the main funder of the arts. It evolved toward the participative democracy paradigm, which “aims towards action instead of the resulting goods, and towards participation in the process instead of consuming its products” (J. Vidal-Beneyto, cited in García Canclini, 1987, p. 50). This notion of evolution in paradigms is strengthened by later discourses on the role of culture and the arts in social development and poverty reduction.

These discourses started to appear in the 1990s in the agendas and diplomacy papers of several international organizations. In 1992 Enrique Iglesias, president of the Inter-American Development Bank, created the “IDB Cultural Center” with the aim of “advancing the concept of culture as a component of development”. Since the appointment of James D. Wolfensohn as president of the World Bank in 1995, the bank has put great emphasis on the role of culture and the arts in social development and in the reduction of poverty. In a study commissioned by the Organization of American States, Claudia Ulloa asserts that “[t]aking appropriate heed of the link between culture and development will be pivotal to the success of future cultural policies, as will the capacity of policy shapers to accomplish results through multi-sectorial intervention”. In the same manner, UNESCO “defends the case of indivisibility of culture and development, understood not simply in terms of economic growth, but also as a means of achieving a satisfactory intellectual, emotional, moral and spiritual existence”.

Comentarios sobre Acción Social por la Música y Política Cultural, Parte 1 (Extraído de mi Ensayo de Maestría)

En los últimos 10 años, alrededor del mundo han aparecido varios proyectos de artes escénicas con un componente de desarrollo social. Esta tendencia debe ser bien examinada por los administradores de las artes, debiendo prestar atención a la forma en la que las organizaciones internacionales que proveen apoyo financiero a programas de desarrollo social estan interactuando con organizaciones de las artes en el Tercer Mundo, dándole forma a un nuevo paradigma de las políticas culturales.

Ya son más de dos decadas desde que Nestor García Canclini presentó el primer análisis de las políticas culturales en America Latina (García Canclini, N. (1987), Políticas Culturales en América Latina (1a. ed.) México, Grijalbo). En su análisis, García Canclini presenta seis paradigmas sobre los orígenes, los agentes, las estructuras organizacionales y las metas de las políticas culturales en los países Latinos. Aunque no es la intención de García Canclini, es fácil esbozar una cierta evolución histórica en estos paradigmas, desde el llamado "mecenazgo liberal" hasta el paradigma de la democracia participativa. El mecenazgo liberal se puede remontar a la Edad Media, aunque auún sobrevive en los Estados Unidos y otros países donde el estado no es el principal patrocinador de las artes. El mecenazgo liberal evoluciono hasta convertirse en democracia participativa, que "apunta más a la actividad que a las obras, más a la participación en el proceso que al consumo de sus productos" (J. Vital-Beyeto, citado en Garcia Canlini, 1987, p.50). Esta noción de una evolución histórica de los paradigmas se refuerza con argumentos posteriores sobre el papel de la cultura y las artes en el desarrollo social y la reducción de la pobreza.

Estos argumentos principiaron a aparecer en los 1990s en las agendas y discursos diplomáticos de varias organizaciones internacionales. En 1992 Enrique Iglesias, presidente del Banco Inter-Americano de Desarrollo creó el "Centro Cultural BID" con el objetivo de "avanzar el concepto de cultura como un componente del desarrollo". Desde que James D. Wolfensohn fué nombrado presidente del Banco Mundial en 1995, el Banco ha puesto especial énfasis en el papel de la cultura y las artes en el desarrollo social y la reducción de la pobreza. En un estudio comisionado por la Organización de Estados Americanos, Claudia Ulloa asegura que "prestar especial atención en el vínculo entre cultura y desarrollo será clave para el éxito de futuras políticas culturales, así como la capacidad de los políticos de alcanzar resultados por medio de la intervención multisectorial". Del mismo modo, UNESCO "defiende el caso de la indivisibilidad de cultura y desarrollo, comprendido no solamente en términos de crecimiento económico, pero tambien como una forma de alcanzar una existencia intelectual, emocional, moral y espiritual satisfactoria".

Saturday, June 10, 2006

Comments on Social Action Through Music and Cultural Policy, Part 2 (From my Masters Essay)

The new approach to culture and social development from international organizations (UNESCO, World Bank, OAS, etc.) is pushing governments to re-think their cultural policies, and arts organizations and artists in these countries to reconsider their views on the purposes of art and their organizations’ missions. Third world countries’ policies for development and culture seem to be led, and even dictated, by the agendas of these international organizations. Organizations like the World Bank, the Organization of American States and the Inter-American Development Bank provide large amounts of economic support and grants to governments and non-profit organizations. Kurt Weyland (Weyland, K. G. (2004). Learning from foreign models in Latin American policy reform). Washington, D.C. Baltimore: Woodrow Wilson Center Press; Johns Hopkins University Press) argues that public policymaking, specially in Latin America appears “to come in waves, as innovation in one country triggers imitation by other nations”. In the case of culture and social development, it seems like the agendas of international organizations also influences on the formation of these trends or “waves.”

As a result, many arts organizations rely on this approach for survival. By presenting a social development mission, they can secure funding from governments and international organizations. Many arts organizations, however, have effectively renovated their missions to attain social mobilization without relying on such funders. These arts organizations are deeply appreciated in societies in which any opportunity for empowerment makes a big difference in the social development of individuals and communities.

The Venezuelan National System of Youth and Children's Orchestras is a great example of social action through the performing arts., although it is not the only one. Many other programs in Third World countries not connected with Venezuela have developed projects to achieve social development, provide effective participation in the arts, and preserve their artistic integrity. (See part 3)

Comentarios sobre Acción Social por la Música y Política Cultural, Parte 2 (Extraído de mi Ensayo de Maestría)

La nueva concatenación de cultura y desarrollo social adoptada por organismos internacionales (UNESCO, OEA, Banco Mundial, etc.) empuja a los gobiernos a reconsiderar sus políticas relacionadas con la cultura y el arte, y a muchas organizaciones para las artes y artistas individuales los lleva aa reconsiderar sus perspectivas sobre las funciones del arte y la misión de sus organizaiones. En general, las políticas de los países considerados tercermundistas parecen estar guiadas, e incluso dictadas por las agendas de estas organizaciones internacionales. Organizaciones com el Banco Mundial, el BID, o la OEA, proporcionan grandes cantidades de apoyo económico y aportes a los gobiernos y a organizaciones no gubernamentales. Kurt Weyland (Weyland, K. G. (2004). Learning from foreign models in Latin American policy reform). Washington, D.C. Baltimore: Woodrow Wilson Center Press; Johns Hopkins University Press) argumenta que el quehacer de las políticas públicas, especialmente en America Latina pareciera "venir en olas, cuando la innovación en un país propicia la imitación en otras naciones". En el caso de la cultura y desarrollo social, pareciera que las agendas de las organizaciones internacionales tambien influyen en la formación de estas "olas". Como resultado, muchas organizaciones para las artes se aprovechan de estos discursos para su sobrevivencia. Al presentar una misión de desarrollo social, estas organizaciones pueden asegurarse fondos de gobiernos y organizaciones internacionales. Por el otro lado, otras muchas organizaciones para las artes han renovado sus misiones para faciliatar moviliacion social sin tener que depender de estos financiamientos. Estas organizaciones son apreciadas en sociedades donde cualquier oportunidad de empoderamiento hace una gran diferencia en el desarrollo social de individuos y comunidades.

El Sistema Nacional de Orquestas Infantiles y Juveniles de Venezuela, es un ejemplo importante de acción social a través de las artes escenicas, aunque no es el único. Muchos otros programas en el paises del Tercer Mundo, sin conexión alguna con Venezuela, han creado programas que propician desarrollo social, proporcionando participacion efectiva en las artes y preservando su integridad artística.

Friday, June 09, 2006

Comments on Social Action Through Music and Cultural Policy, Part 3 (From my Masters Essay)

As mentioned before, along with the Venezuelan System of Youth and Children;s Orchestras and its replications in Latin America, several organizations around the world have developed projects to achieve social development, provide effective participation in the arts, and preserve their artistic integrity.  These include the African Children’s Choir, which focuses on children aged seven to eleven who have lost one or both parents. Having originated in Uganda in 1984, it is supported by the Foundation for Life, a Christian organization, and now has programs in Rwanda, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Sudan and Kenya.

These include the African Children’s Choir, which focuses on children aged seven to eleven who have lost one or both parents. Having originated in Uganda in 1984, it is supported by the Foundation for Life, a Christian organization, and now has programs in Rwanda, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Sudan and Kenya.  In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the Afro-reggae Cultural Group was founded in 1993 with the mission “to promote social inclusion and social justice through art, Afro-Brazilian culture and education, bridging differences and serving as foundations to citizenship sustainability”. Afro-reggae gives instruction in traditional Brazilian percussion and dance to youth at risk from the “favelas” in Rio de Janeiro to keep them from joining drug-dealing gangs, and by giving them tools to empower other youth. They receive financial support from international and local organizations as well as from U.S. Foundations.

In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the Afro-reggae Cultural Group was founded in 1993 with the mission “to promote social inclusion and social justice through art, Afro-Brazilian culture and education, bridging differences and serving as foundations to citizenship sustainability”. Afro-reggae gives instruction in traditional Brazilian percussion and dance to youth at risk from the “favelas” in Rio de Janeiro to keep them from joining drug-dealing gangs, and by giving them tools to empower other youth. They receive financial support from international and local organizations as well as from U.S. Foundations.  The violin program at the Gandhi Ashram School in Kalimpong in the Indian Himalayas teaches children from the Biswa Karma class, one of the lowest in the Hindu caste system. Support and instruction to learn violin, and opens educational and social mobilization opportunities. The program, began in the early 1990s, is supported by Indian, German and Canadian donations.

The violin program at the Gandhi Ashram School in Kalimpong in the Indian Himalayas teaches children from the Biswa Karma class, one of the lowest in the Hindu caste system. Support and instruction to learn violin, and opens educational and social mobilization opportunities. The program, began in the early 1990s, is supported by Indian, German and Canadian donations.  Worth mentioning also is Guatemala's Caja Ludica, in which I taught a bit, coordinated a percussion troupe for a while, and co-produced and performed in several montages. I miss them...

Worth mentioning also is Guatemala's Caja Ludica, in which I taught a bit, coordinated a percussion troupe for a while, and co-produced and performed in several montages. I miss them...

Comentarios Sobre Acción Social por la Música y Políticas Culturales, Parte 3 (De mi Ensayo de Maestría)

Como mencioné anteriormente, además del sistema de Orquestas de Infnatiles y Juveniles de Venezuela y sus réplicas en América Latina,varias organizaciones alrededor del mundo han desarrollando proyectos para facilitar desarrollo social, proveer participación efectiva en las artes y preservar su integridad artística.  Estos incluyen el Coro de Niños de Africa, que se enfoca en niños de siete a once años que han perdido a uno o ambos de sus padres. Originado en Uganda en 1981, es apoyado por la Fundación para la Vida, una asociación Cristiana, y ahora tiene programas en Ruanda, Sudáfrica, Nigeria, Ghana, Sudán y Kenia.

Estos incluyen el Coro de Niños de Africa, que se enfoca en niños de siete a once años que han perdido a uno o ambos de sus padres. Originado en Uganda en 1981, es apoyado por la Fundación para la Vida, una asociación Cristiana, y ahora tiene programas en Ruanda, Sudáfrica, Nigeria, Ghana, Sudán y Kenia.  En Río de Janiero, Brasil, el Grupo Cultural Afro-Reggae fue fundado en 1993 con la misión de "promover la inclusión y la justicia social, usando arte, cultura afro-brasileña y educación como herramientas para crear puentes que unan las diferencias y sirvan como base para el sustento y para ejercitar la ciudadanía". Afro-Reggae ofrece instrucción en percusión y danza tradicional brasileña, a jóvenes en riesgo de las favelas en Río de Janeiro, para prevenir que se unan a pandillas de traficantes de drogas y proporcionandoles herramientas para empoderar a otros jóvenes. Afro-reggae recibe apoyo económico de organizaciones locales e internacionales así como de Fundaciones privadas en Estados Unidos.

En Río de Janiero, Brasil, el Grupo Cultural Afro-Reggae fue fundado en 1993 con la misión de "promover la inclusión y la justicia social, usando arte, cultura afro-brasileña y educación como herramientas para crear puentes que unan las diferencias y sirvan como base para el sustento y para ejercitar la ciudadanía". Afro-Reggae ofrece instrucción en percusión y danza tradicional brasileña, a jóvenes en riesgo de las favelas en Río de Janeiro, para prevenir que se unan a pandillas de traficantes de drogas y proporcionandoles herramientas para empoderar a otros jóvenes. Afro-reggae recibe apoyo económico de organizaciones locales e internacionales así como de Fundaciones privadas en Estados Unidos.  El programa de Violín en la Escuela Ashram Gandhi en Kalimpong, en los Himalayas de la India, enseña a niños de la clase "Biswa Karma", una de las más bajas en el sistema de castas Hindú. Ellos ofrecen apoyo e instrucción para aprender el violín, y les abre oportunidades de educación y mobilización social. El programa, que se inicio en la década de 1990, está financiada por donaciones de India, Alemania y Canadá.

El programa de Violín en la Escuela Ashram Gandhi en Kalimpong, en los Himalayas de la India, enseña a niños de la clase "Biswa Karma", una de las más bajas en el sistema de castas Hindú. Ellos ofrecen apoyo e instrucción para aprender el violín, y les abre oportunidades de educación y mobilización social. El programa, que se inicio en la década de 1990, está financiada por donaciones de India, Alemania y Canadá.  No puedo dejar de mencionar al Colectivo Caja Lúdica de Guatemala, en el que dí algunas clases, coordiné un grupo de percusión por algún tiempo y co-produje y/o toqué en un par de montajes. Cómo los extraño...

No puedo dejar de mencionar al Colectivo Caja Lúdica de Guatemala, en el que dí algunas clases, coordiné un grupo de percusión por algún tiempo y co-produje y/o toqué en un par de montajes. Cómo los extraño...

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

Philharmonic of the Americas

Filarmonica de las Americas

Last night I attended the concert of the new Philharmonic of the Americas, under de baton of its founder, 24-year-old Alondra de la Parra, at Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center. It featured Venezuelan prodige Edicson Ruiz's New York debut premiering Paul Desanne's Bass concerto. I am no music critic, so here is just my humble take on it: For Ruiz it was risky to debut with a new (very new) piece. It needed more work. A lot of times the bass could not be heard at all, percussion was TOO loud (and I am a percussionist, so go figure). As for the rest of the concert, Revueltas' Redes was played with great energy and drama. The audience got turned on by Bernstein's Overture to West Side Story. That Latin "thing" that emanates for a performer really makes a difference. In this case, de la Parra's Latin "think" made this a very special and unique performance. I just regret that Edicson's performance didn't blow my mind...

_________________________________

Anoche fui al concierto de la nueva Filarmonica de las Americas, dirigida por Alondra de la Parra, de 24 años, en Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center. Se presento al prodigio venezolano Edicson Ruiz en su debut como solista en Nueva York, con el Concierto para Contrabajo de Paul Desanne. No pretendo ser critico de musica, pero aqui va mi humilde opinion: Para Ruiz fue un poco arriesgado debutar con una pieza nueva (muy nueva). Necesitaba mas trabajo. Muchas veces el contrabajo no se escuchaba en lo absoluto, y la percusion fuera de balance (y eso que soy percusionista, no deberia tener objeciones al respecto). Por lo demas, Redes de Silvestre Revueltas sono energico y dramatico, como debe de ser. Pero el publico se encendio con la Obertura de West Side Story de Bernstein. Esa "cosa" latina que emana de un interprete de veras hace la diferencia. En este caso, la "cosa" latina de de la Parra hizo de esta una presentacion especial y unica. Solo lamento que el debut de Edicson no me haya impresionado...

Monday, June 05, 2006

Jogging

Hoy rompi mi propio record. Otra vez tome el tren 1 a Battery Park (el extremo sur de Manhattan), y corri hasta la calle 120. En total corri como 8.5 millas, en 1.5 horas. Sobrevivi.

____________________________

Today I broke my own records. Once again, I took the 1 train to Battery Park (the South tip of Manhattan) and ran up to 120th Street. I ran about 8.5 miles in 1.5 hours. I survived.

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Español,

NYC,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Friday, June 02, 2006

Historia al reves

History backwards

A veces pienso que nos deberian haber ensenado la historia de las cosas al reves. Eso incluye historia universal, historia del arte, de la musica, de la arquitectura, de la literatura...Por que no estudiar filosofia principiando por las corrientes de pensamiento actuales: Escabar profundamente en la teoria de como pensamos hoy, y porque pensamos asi, y luego empezar a ver de donde chingados viene nuestra forma de pensar, y luego de tener un marco de teoria que nos conecte con el pasado inmediato, escarbar esas otras corrientes, de donde vienen esas otras formas de pensar, y mientras avanzamos a la universidad, quizas, si es relevante, estudiar filosofia clasica griega. Lo mismo para todas las cosas que tenemos que estudiar. En vez de llegar a la universidad aburridos de oir teorias antiguas, sin ganas ya de aprender sobre las nuevas teorias que son mas relevantes para nuestros dias.

Estos dias estoy leyendo "The Art Firm", de Pierre Guillet de Monthoux, que examina corrientes filosoficas que son relevantes para la gerencia de las artes. Al leerlo, reconozco que la forma de pensar europea (en general) no considera ni siquiera remotamente el pensamiento de una sociedad que tiene que vivir dia a dia con extrema pobreza, injusticia y desigualdad. Me encantaria poder empezar desde ahi, y recorrer en forma regresiva las corrientes filosoficas nos han hecho ser como somos y pensar como pensamos hoy. Ciertamente no son los mismos caminos que en Europa...simplemente no hay espacio para comparar...

_______________

Sometimes I think that we should have been taught the history of things backwards. That includes world history, art, music, architecture, literature history...Why not study the current philosophical trends? dig in in depth into the way we do think today, why do we think this way. After we have a broad understanding of that, we could start to study where the fuck did this way of thinking came from, and after we have a theoretical frame that connects us to the immediate past, dig into those other philosophical trends. As we advance in our education, perhaps, if it is relevant, we would end up studying the classical greek philosophers. This instead of arriving to college already bored of being forced to study ancient thought to which we have no relation whatsoever, and with no interest of learning current philosophical trends.

These days I've been reading "The Art Firm" by Pierre Guillet de Monthoux, which examines the philosophical trends that are relevant to arts management. As I read it, I realize that European thought (in general) does not consider even remotely the philosophical thought of societies and cultures dealing on a daily basis with extreme poverty, injustice and inequity. I would like to start from there, and go through the philosophical trends that make us be the way we are and think today. Certainly they are not the same paths...There is no room for comparison.

1 comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Español,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, May 31, 2006

untitled/sin titulo

Hoy estaba pensando...En las noticias en linea de Guatemala no se lee ya mucho acerca de misioneros evangelicos. Aun asi, aca oigo comentarios de gente (Noeyorquinos, por supuesto) que van por turismo, y se sorprenden de ver los grupos de misioneros con sus caras de hiper-felicidad y camisetas coloridas con dibujitos hechos por ninos, representando familias "tradicionales" felices y agarraditos de las manos... Mis amigos que se han subido a un avion y ven esto salen horrorizados...

Ojala que estas invasiones a Latinoamerica no suciten guerras culturales como la que esta viviendo Estados Unidos internamente.

Today I was wondering...In the Guatemalan news online you don't read anymore much about evangelical missionaries. However, I hear people here (New Yorkers, of course) going on vacations and finding a plane-full of missionary groups, with the hyper-happy faces and colorfull t-shirts with children's drawings of happy "traditional" families, all holding their little hands...My friends have arrived in Guatemala horrorized...

Hopefully these invasions in Latin America won't result in the same culture wars that are going on in the U.S.

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Español,

Guatemala

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Memorial Day

I decided to take the 1 train to South Ferry and jog back home (up to 72nd Street), about 6.4 miles. It was a nice pleasant jog. Interesting landscapes and people (like a jogger in dippers). I could have gone further. Will do it soon.

__________

Decidi tomar el tren 1 al Ferry Sur, y trotar de regreso a casa (Hasta la calle 72), unas 6.4 millas (10.23km). Fue placentero. Paisajes y gente interesante (tal como el corredor en pañales). Podria haber seguido corriendo. Lo intentaré pronto.

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Español,

NYC,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Commencement Day/Dia Graduacion

Hoy almorcé comida china para llevar. Mi galleta de la fortuna dice así: "Ser capaz de ver hacia atrás nuestro propio pasado con satisfacción es vivir dos veces". Que venga la tercera!

Today I had Chinese takeout. My fortune cookie says: "To be able to look back upon one's past life with satsfaction is to live twice." Bring on the third one!

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Español,

NYC,

Other stuff,

Otras Cosas

![]()

![]()

Friday, January 27, 2006

The Venezuelan Orchestras

On December 2004, Sir Simon Rattle, music director of the Berlin Philharmonic, conducted the over-two-hundred-piece Venezuela National Youth Symphony, performing Mahler’s Second Symphony. After the dress rehearsal, Rattle told the orchestra: “I don’t think there is anything more important going on in music in the world right now than what is happening in Venezuela. You are lucky, but we are unbelievably lucky and the rest of the world has so much to learn from this, because I think this is the future of music.”

The orchestra that Rattle conducted, is the selection of the finest young musicians in Venezuela, coming from disadvantaged homes in small towns and poor neighborhoods. They are the product of an orchestra system that was founded 30 years ago, and has begun its internationalization, starting in Latin America, but with the strength to spread globally.

After more than five years of involvement with the Guatemalan offshoot of the Venezuelan Orchestra System, in July I decided it was time to visit Caracas and make new contacts, do research, and visit friends and colleagues. Most importantly, I wanted to see with my own eyes the progress of a movement that I have been involved with for a few years in my own country.

Our first contact with the Venezuela Orchestra System was back in 1996, when one of its representatives visited Guatemala City to find and persuade some professional musicians and leaders to start a similar system in Guatemala. The status of symphony orchestra in Guatemala then was not much different from what it was in Venezuela in 1975, when Dr. Jose Antonio Abreu –a conductor, economist, savvy politician, and one of the most charismatic personalities in Latin America– started the Venezuelan orchestra system.

The first members of this youth symphony, later named Orquesta Sinfónica de la Juventud Venezolana Simón Bolivar (“Simon Bolivar Venezuelan Youth Symphony Orchestra”) never dreamed where they were headed. In 1975, professional symphonies in Venezuela offered limited opportunities for a few talented musicians. Classical music professionals were reluctant to question the traditional music establishment, even though things were not moving forward artistically and economically and audiences were declining.

In Guatemala, even those of us willing to look for new options, had many questions about the Venezuelan system. When we were presented with it for the first time, a common response was that “in Guatemala it couldn’t be done”. Poverty, corruption, low educational levels, and other problems made the Venezuelan system look utopian. But those, problems didn’t faze the Venezuelans.

A year later, 9 musicians of the Simón Bolivar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela led by Maestro Ulyses Ascanio, proved that things could get done in Guatemala. Beginning from scratch, and despite of the disapproval of the conservative music professors, and some accusations of child exploitation, the brand new Guatemalan Youth Symphony, later re-named Jesús Castillo Symphony Orchestra, debuted successfully. After ten days of 12 hour-a-day rehearsals the orchestra performed repertoire that the members never dreamt of playing. A decade later, they remember it as one of the happiest and most fulfilling experiences of their lives. Lesson learned: It can be done in Guatemala. Actually, it can be done anywhere. This is what the Venezuelans have been doing for the past 30 years in their country and in several others in Latin America and the Caribbean.

30 years and counting

In 1975, Abreu invited a group of 11 students to start a new Youth Symphony. During the first rehearsal, Abreu offered the students a tour to Mexico. The eleven attendees were enthusiastic, but skeptical. A few months later, and despite strong criticism for its unorthodox practices, a full youth symphony orchestra was ready to make the trip.

A year later, the same orchestra participated in a youth symphony festival in Aberdeen, Scotland, conducted by Carlos Chávez, who traveled from Mexico exclusively to prepare them. The quick success of the orchestra and the improvement of its members motivated them to believe Dr. Abreu’s vision, even if it still seemed utopian. Hard work in the face of ongoing criticism made them adopt the phrase “to play and to struggle” as their motto. Some of these students would travel regularly for long hours by bus to their hometowns, where they started small orchestras just like the one they just founded in Caracas. Some of them remember this as a precarious time. These new orchestras were far from a professional level, but they were causing a deep impact in their towns. As Abreu has said “the orchestras turned into the souls of the communities.”

A new system was born. The “State Foundation for the National System of Youth and Children’s Orchestras of Venezuela” (FESNOJIV) was created in 1979 as its organizational base. It has survived the severe political, economic and social changes in Venezuela over the last 30 years with full support of both the government and the private sector. The system has grown exponentially. By 2005, it included 210 orchestral ensembles serving about 240,000 students.

For over 10 years they have looked beyond Venezuelan boundaries. Missions like the one in Guatemala have been sent to Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil, Argentina, El Salvador, Honduras, Panama, Dominican Republic, Mexico and Trinidad and other islands of the Caribbean. Joint programs like the Symphony of the Americas, the Latin America Youth Symphony, the Mercosur Youth Symphony and the Youth Symphony of the Andes, are replicas of the model used in Venezuela.

Between 1998 and 2002, the Venezuela Children’s Orchestra toured Europe several times with gigantic success. In 2002 Germany and Venezuela initiated an orchestral exchange program, which includes periodic seminars by German professors in Venezuela. In 2004, Edicson Ruíz, a 17-year-old bassist from the orchestra system in one of the poorest neighborhoods in Caracas won a double-bass audition at the Berlin Philharmonic, becoming the youngest musician in its history.

The principles of the Venezuelan System

When they speak of their system, Venezuelans are talking about a broad network of musicians, educators and administrators, as well as music education centers and symphony orchestras –children’s, youth and professional. It includes centers for instrument construction and maintenance and for filming and archiving the main concerts, seminars and master classes. This network functions under the same organizational culture, philosophy and principles, dictated by FESNOJIV, guided by its founder, Dr. Abreu, who devotes close and constant attention to the development of each activity.

The system can be viewed from two perspectives: the purely artistic and the social. Artistically, according to Ascanio, “the principle is to turn the musical practice into a collective experience. The orchestra becomes a classroom and a music laboratory in which students find the reason to practice. The interaction with their peers gives them a stronger motivation to practice and study.” In Venezuela, this approach was revolutionary and had a lot of opposition when it started. “Traditionally, music practice was ruled by a system of conservatories which produced a small number of musicians. There was a lack of the less popular instruments. Most students chose violin and piano while other instruments were ignored. The orchestra functioned around the music schools as a supplementary course since students were being prepared for solo careers.” After finishing their academic preparation, musicians would find themselves jobless, frustrated, and faced with having to start new careers.

The system doesn’t expect to graduate thousands of professional musicians. It only expects to make better citizens who happen to play in remarkably good orchestras. In an interview in Chefi Borzacchini’s recently published book Venezuela Sembrada de Orquestas (“Venezuela Seeded with Orchestras”) Igor Lanz, FESNOJIV’s executive director stated, “You cannot speak of desertion in this system. What is important about it is that whoever enters can have multiple choices, from the professional and musical per se, to any other possible choice.” Students not only become remarkable musicians, but also are offered a broader perspective of life and careers opportunities.

This, along with the large number of students served, turns the orchestra system into a significant social force. The system often presents itself as a movement of social action through music. It concentrates on disadvantaged youth and children from troubled or lower income backgrounds. For them, playing in an orchestra with high artistic goals offers more benefits than the hope of becoming a classical music superstar. In the T.V. documentary “Resurrección en Movimiento” (Resurrection in Motion), produced by Venezuela’s Vale TV, Dr. Abreu talks about an economic principle called “the vicious cycle of poverty”: “A country is poor because it is poor, a man is poor because he is poor, and since he is poor he cannot get prepared, he cannot access education, and therefore he remains poor. The orchestra breaks through this cycle of material poverty,” he continues. “By being part of an orchestra, a child that is materially poor, becomes spiritually rich, so he begins to aspire and struggles to be better, and generates an energy that his material poverty doesn’t provide”.

Ascanio explained how he compares playing in an orchestra to living in society: “In the orchestra there are ranks, hierarchies, obligations, rights, discipline, incentives, healthy competition, and each has an important role for the whole, just like living in a family: you enjoy certain liberties but have to respect certain limits.”

The students carry all those values into their households and communities. With an average of 5 members per family, the orchestra system currently reaches over a million Venezuelans. It truly plays an important role in the improvement of society; it is a real community outreach. It is worth noting that FESNOJIV is part of the Ministry of Health and Social Development, which provides most of its working budget.

Organizational Structure and Teaching Methods

FESNOJIV’s system is organized through a network of music centers, which are mostly located in poor neighborhoods and towns, called núcleos –96 of them around the country. Each núcleo has at least one orchestra and offers free permanent music lessons, using borrowed or donated instruments. The main teaching method is the intensive seminar, like the one brought to Guatemala. Such seminars are organized constantly. Sometimes they specialize in a specific orchestral repertoire, and sometimes in a specific instrument or section to focus on technique and performance. Intensive seminars offer a chance for larger interaction among established ensembles all over the country. These seminars are frequently taught and led by top musicians from Venezuela, Europe and the U.S. Recently, and after FESNOJIV established a close relationship with the Berlin Philharmonic, many of their musicians led seminars specializing in each instrument of the orchestra.

An important strength of the system is the speed at which students assimilate new skills and face new and difficult repertoire. This is in part because of their teaching method: when a child learns a skill, he or she has to learn it so well that it can immediately be taught to another student. It is common to find students who are only a few years younger than the teacher and have only a few years less experience. This method, combined with constant participation in seminars and festivals, ensures that the students’ progress is not only fast and effective, but also highly competitive and constantly evaluated.

The clearest proof of this progress was the 1998 National Children’s Orchestra –a selection of the best young musicians in the country. Soon after growing in age to become the National Youth orchestra, they grew in quality to become a professional-level orchestra. Today, their members, mostly in their late teens and early twenties, have been following the course of the Simón Bolivar Symphony founding members. The same people who reached international recognition by “playing and struggling” couldn’t just ignore the quality and needs of their pupils. But the Simón Bolivar Orchestra, the top professional ensemble in the system, could neither absorb a whole new orchestra, nor reject such a talented group of young musicians. The solution was to establish a temporary “second” Simón Bolivar Symphony. The original founders’ orchestra is known as Simón Bolivar “A”. The youth orchestra is Simón Bolivar “B”.

Many of their musicians teach individuals and groups, lead seminars, conduct orchestras and other ensembles, and even play a multiple roles as musician/administrator/music entrepreneurs in Caracas or elsewhere. During my visit to Caracas, Simón Bolivar “A” was playing its regular season, while the brass section of Simon Bolivar “B” was on tour in South America, and the rest joined the Youth Symphony of the Americas as guests during its performances in Caracas.

One morning, I had the chance to visit the Núcleo Montalbán, in the outskirts of Caracas. On this day, at the start of the school vacation, Montalbán was the base for a Caracas Youth Symphony’s seminar to prepare a new repertoire for its upcoming national tour conducted by Ulyses Ascanio. The tour repertoire included Glinka’s Russlan and Ludmilla Overture, and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Russian Easter Overture. Usually, this núcleo is the headquarters for the early childhood music education program (Sistema de Orquestas pre-Infantiles de Venezuela).

At Montalbán, the program’s director Susan Simán, explained the system that she has designed and implemented as a prototype that has been followed in seven other regions, and was recently introduced in other countries. The Children’s program consists of five levels, starting at 2 years old, with a preparatory course, using a combination of the traditional music education methods (Orff, Kodaly, Dalcrosse, etc.), all focused on orchestra performance, including the basic skills, values and discipline needed to work in an ensemble. At this level, students use their voice, simple percussion instruments and recorder flutes. Since children are so young, parents have to participate and play in a “parallel” ensemble, but are only expected to play the same as their children.

In the subsequent levels, children progress to play their chosen orchestral instruments, until they reach the highest level in the program: the children’s orchestra. After reaching this level, students can continue with private lessons and participate in seminars. The repertoire throughout the program consists of sets of works that run from simple orchestral pieces and arrangements to advanced repertoire like Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony and Revueltas’ Sensemayá. These sets of works are used as standards nationally, and have been chosen to focus on specific skills that will speed the learning process.

At the concert of the Youth Symphony of the Americas, I was able to put faces and voices to familiar names. Gustavo Dudamel, 23 years old and a product of the orchestra system, was about to conduct that afternoon. In the lobby of the Teresa Carreño Theater, long lines of adults, adolescents and children were waiting to get in the hall, and more were desperately looking for spare tickets. At the concert I was almost deafened by the cheers and high-pitched applause of a group of children sitting behind me, excited to see Dudamel conducting Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra. At the intermission I went to meet them. They were the members of the Fundación del Niño Children’s Orchestra from Miranda, an orchestra that plays one or two concerts each month with new repertoire. Two of their members –Erick Gutierrez, percussion, 13, and Francis Gagliardi, French horn, 11, explained their excitement at coming to Caracas and attending the Teresa Carreño Theater for the second time. One of their most memorable experiences, they told me, was being part of a massive orchestra that played for Claudio Abbado last year.