It is one of those funny coincidences that Rufus Wanwright's Tribute to Judy Garland Concert in Carnegie Hall happened only a couple of days before the opening of a big Dada exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. I had the fortune to attend the first of two concerts offered by Rufus. Since I am (still) reading The Art Firm (see "History Backwards", in this blog), I spent the concert trying to look at the big picture: Rufus is not a great singer, I never heard Judy Garland's Carnegie Hall concert (which Rufus reproduced, at least in the order of the songs and by using the same orchestra arrangements, transposed). So no, it was not a great concert. "Is this Art or entertainment?" I kept thinking. Then I thought of it as a performance art piece, less about beauty and technique, but more about making a political statement. As Stephen (Holden) told me, it IS a big deal that a man is standing there doing what most of the people in the audience have fantisized about (I think 85-90% of the audience was gay, over 30).

It is one of those funny coincidences that Rufus Wanwright's Tribute to Judy Garland Concert in Carnegie Hall happened only a couple of days before the opening of a big Dada exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art. I had the fortune to attend the first of two concerts offered by Rufus. Since I am (still) reading The Art Firm (see "History Backwards", in this blog), I spent the concert trying to look at the big picture: Rufus is not a great singer, I never heard Judy Garland's Carnegie Hall concert (which Rufus reproduced, at least in the order of the songs and by using the same orchestra arrangements, transposed). So no, it was not a great concert. "Is this Art or entertainment?" I kept thinking. Then I thought of it as a performance art piece, less about beauty and technique, but more about making a political statement. As Stephen (Holden) told me, it IS a big deal that a man is standing there doing what most of the people in the audience have fantisized about (I think 85-90% of the audience was gay, over 30).

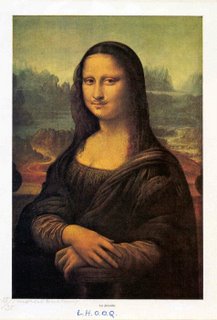

Then, Duchamp and his moustached Mona Lisa (Called "L.H.O.O.Q", read in French: "Elle a chaud au cul", could be translated as "She's got a hot ass") came to my mind. I found it hilarious: Duchamp's Moustached Mona Lisa is to the original Mona Lisa, what Rufus' tribute concert is to Judy Garland's 1961 Carnegie Hall concert.

Then, Duchamp and his moustached Mona Lisa (Called "L.H.O.O.Q", read in French: "Elle a chaud au cul", could be translated as "She's got a hot ass") came to my mind. I found it hilarious: Duchamp's Moustached Mona Lisa is to the original Mona Lisa, what Rufus' tribute concert is to Judy Garland's 1961 Carnegie Hall concert.

As for the MoMA exhibit, which opens this weekend, I won't be missing it!

Friday, June 16, 2006

Rufus Wainwright: L.H.O.O.Q.

0

comments/Comentarios

Labels:

English,

Music,

NYC,

Opinion

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

De donde vienen las politicas del arte?

Siempre me dió la impresión que en Guatemala se esperaba que las políticas culturales (y del arte) fueran un librito con instrucciones con todas las soluciones para el sector, y que nadie se había tomado la molestia de escribirlas. A finales de los 1990s iniciaron los congresos, talleres y planes estratégicos para discutir e idealmente producir este librito (al menos, porque implementarlas realisticamente sería otra historia). En el documento final "Políticas Culturales y Deportivas Nacionales", publicado en 2000 por el Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, la palabra "arte" se menciona tres veces, y la palabra "artista" seis.

En próximos artículos, voy a intentar examinar con detalle las políticas de las artes en Guatemala. Y no me refiero solamente a las que fueron producto de estos congresos, seminarios y planes estratégicos, sino ademas de todas las demas que andan flotando, o estan escondidas por ahí, y nadie ha sacado provecho de ellas. Espero encontrarme con buenas sorpresas. Pero, tanto en Guatemala, como en otros países, ¿de dónde vienen las políticas de las artes? Principalmente, estan hechas de leyes tanto nacionales como locales y acuerdos diplomáticos y regulaciones internacionales. Muchas no tienen nada que ver con arte o cultura: Leyes de impuestos, tratados de libre comercio, regulaciones urbanas, leyes en educación y desarrollo social. Aun así, se deben considerar qué "fuerzas" tienen influencia en el quehacer de las artes, y se deberían considerar como los motores de las políticas de arte. Yo me atravería a ponerlas en cuatro categorias:

1. Regulaciones y leyes que fueron ideadas con fines ideológicos/políticos y/u organizacionales.

2. Preservación de tradiciones, costumbres y cánones. (Cultura local y global, tradiciones y cánones artísticas)

3. Tendencias del Mercado de las Artes (qué, cuándo, cómo y cuánto arte se ofrece, y quién esta dispuesto a "consumirlo", bajo qué condiciones, con qué frecuencia, a qué costo, etc.)

4. Movimientos Sociales (movimientos de artistas, u organizaciones que prentenden cambiar el status quo del quehacer de las artes, y en consecuencia producen cambios en cualquiera de los tres factores anteriores)

Where do Arts policies come from?

I always had the impression that in Guatemala people expected cultural (and arts) policy to be a little book of instructions with all the solutions to the arts sector, and that no one had taken time to get to write them. Then they started the strategic plannings, seminars and congresses in order to produce this so-expected little book. In the final document, the word "art" is mentioned less than 10 times, I think (I may be wrong, but that is the impression I got when I checked the document that was out there for a while). En future articles, I will try to examine in detail the policies related to the arts in Guatemala. And I am not refering only to the ones that are a product of those strategic planning seminars and congresses, but also other laws that are floating out there, or hiden somewhere and nobody has taken advantage of them. I look forward to find good surprises. But, where do arts policies come from? Mainly they come from the legal system, both national and local, and diplomacy agreements and international regulations. A lot of them have nothing to do with arts or culture. Still, one should consider which "forces" have an infuence in arts making, and should be considered the "engines" of arts policy. I can think of four categories:

1. Regulations and laws (created with ideological/political and/or organizational goals)

2. Local culture (Traditions and customs of the people that practices, attends and/or supportsthe arts)

3. Arts market trends (what, when, how and how much art is out there, and who is willing to "consume" it, under what conditions, how often, to what cost, etc)

4. Social movements (movements or artists or arts organizations that pretend to change the status quo of arts making, and in consequence produce changes in any of the three above mentioned factors)

Sunday, June 11, 2006

Comments on Social Action Through Music and Cultural Policy, Part 1 (From my Masters Essay)

In the last 10 years, several performing arts projects with a social development component have appeared throughout the world. Arts administrators should be aware of these trends and pay close attention to how international organizations that provide financial support to social development programs are interacting with arts organizations in the Third World, and giving shape to a new cultural policy paradigm.

It has been almost two decades since Nestor Garcia Canclini offered the first broad critical analysis of cultural policies in Latin America (García Canclini, N. (1987). Políticas culturales en América Latina [Cultural Policy in Latin America] (1a. ed.). México: Grijalbo). In his analysis, he outlines six paradigms for the origins, agents, organizational structures and goals of cultural policies in Latin countries. Although it is not Garcia Canclini’s intention, it is easy to trace a certain historical evolution in those paradigms by examining the first –mecenazgo liberal (liberal patronage)– and the last –democracia participativa (Participative Democracy). The liberal patronage paradigm can be traced back to the Middle Ages, although it still survives in the United States and other countries where the state is not the main funder of the arts. It evolved toward the participative democracy paradigm, which “aims towards action instead of the resulting goods, and towards participation in the process instead of consuming its products” (J. Vidal-Beneyto, cited in García Canclini, 1987, p. 50). This notion of evolution in paradigms is strengthened by later discourses on the role of culture and the arts in social development and poverty reduction.

These discourses started to appear in the 1990s in the agendas and diplomacy papers of several international organizations. In 1992 Enrique Iglesias, president of the Inter-American Development Bank, created the “IDB Cultural Center” with the aim of “advancing the concept of culture as a component of development”. Since the appointment of James D. Wolfensohn as president of the World Bank in 1995, the bank has put great emphasis on the role of culture and the arts in social development and in the reduction of poverty. In a study commissioned by the Organization of American States, Claudia Ulloa asserts that “[t]aking appropriate heed of the link between culture and development will be pivotal to the success of future cultural policies, as will the capacity of policy shapers to accomplish results through multi-sectorial intervention”. In the same manner, UNESCO “defends the case of indivisibility of culture and development, understood not simply in terms of economic growth, but also as a means of achieving a satisfactory intellectual, emotional, moral and spiritual existence”.

Comentarios sobre Acción Social por la Música y Política Cultural, Parte 1 (Extraído de mi Ensayo de Maestría)

En los últimos 10 años, alrededor del mundo han aparecido varios proyectos de artes escénicas con un componente de desarrollo social. Esta tendencia debe ser bien examinada por los administradores de las artes, debiendo prestar atención a la forma en la que las organizaciones internacionales que proveen apoyo financiero a programas de desarrollo social estan interactuando con organizaciones de las artes en el Tercer Mundo, dándole forma a un nuevo paradigma de las políticas culturales.

Ya son más de dos decadas desde que Nestor García Canclini presentó el primer análisis de las políticas culturales en America Latina (García Canclini, N. (1987), Políticas Culturales en América Latina (1a. ed.) México, Grijalbo). En su análisis, García Canclini presenta seis paradigmas sobre los orígenes, los agentes, las estructuras organizacionales y las metas de las políticas culturales en los países Latinos. Aunque no es la intención de García Canclini, es fácil esbozar una cierta evolución histórica en estos paradigmas, desde el llamado "mecenazgo liberal" hasta el paradigma de la democracia participativa. El mecenazgo liberal se puede remontar a la Edad Media, aunque auún sobrevive en los Estados Unidos y otros países donde el estado no es el principal patrocinador de las artes. El mecenazgo liberal evoluciono hasta convertirse en democracia participativa, que "apunta más a la actividad que a las obras, más a la participación en el proceso que al consumo de sus productos" (J. Vital-Beyeto, citado en Garcia Canlini, 1987, p.50). Esta noción de una evolución histórica de los paradigmas se refuerza con argumentos posteriores sobre el papel de la cultura y las artes en el desarrollo social y la reducción de la pobreza.

Estos argumentos principiaron a aparecer en los 1990s en las agendas y discursos diplomáticos de varias organizaciones internacionales. En 1992 Enrique Iglesias, presidente del Banco Inter-Americano de Desarrollo creó el "Centro Cultural BID" con el objetivo de "avanzar el concepto de cultura como un componente del desarrollo". Desde que James D. Wolfensohn fué nombrado presidente del Banco Mundial en 1995, el Banco ha puesto especial énfasis en el papel de la cultura y las artes en el desarrollo social y la reducción de la pobreza. En un estudio comisionado por la Organización de Estados Americanos, Claudia Ulloa asegura que "prestar especial atención en el vínculo entre cultura y desarrollo será clave para el éxito de futuras políticas culturales, así como la capacidad de los políticos de alcanzar resultados por medio de la intervención multisectorial". Del mismo modo, UNESCO "defiende el caso de la indivisibilidad de cultura y desarrollo, comprendido no solamente en términos de crecimiento económico, pero tambien como una forma de alcanzar una existencia intelectual, emocional, moral y espiritual satisfactoria".

.jpg)